A few weeks before the 1999 Seattle WTO shutdown actions, Punk Planet Magazine circulated a call for someone to cover the protests for their next issue. I eagerly volunteered and was delighted when they asked me to do it. In the following weeks, I filled a waterproof notebook with notes on everything in which I was involved and everything I heard from people around me. At the end of each day, I tore out the pages I had filled in case I were to be arrested the next day. And once the protests ended, I spent a week in front of my computer piecing my notes together into a day-by-day account. I was still recovering from tear gas inhalation, my ears were still ringing from concussion grenades, and I was anxiously waiting for some friends to get out of jail. Punk Planet published that piece in early 2000 and, a decade later, a revised version was included in The Battle of the Story of the “Battle of Seattle”. In 2019, anticipating the 20th anniversary of the Seattle protests, I spent several months building it out further by going over narratives from other organizers, reviewing oral history transcripts, and incorporating crucial pre-Seattle movement history. While I recognize that there’s still a lot missing from this account, my hope is that it at least conveys the scale, sequence, and significance of what happened – not as nostalgia, but as a contribution to ongoing transformative movements. I wrote this piece for the Shutdown WTO Organizers’ History Project and I am so honored that it is also featured on the website of Upping the Anti – a journal born from the cycle of struggle associated with the Seattle protests.

On Tuesday, November 30, 1999, I was standing in downtown Seattle on

6th Avenue between Pike and Union – an unremarkable place amidst remarkable

circumstances. Directly in front of me stood a reinforced line of police

officers in full body armor, carrying truncheons, rubber bullet guns, and

grenade launchers. All around me, hundreds of protesters packed into a human

wall taking up half a block. And directly behind us in the middle of an

intersection, at least another hundred people protectively surrounded a large

wooden platform underpinned by metal pipes. Locked inside each pipe was the arm

of an activist. Resolute and defiant, we were all there to shut down the World

Trade Organization Ministerial meetings that were scheduled to begin that day.

“This is the Seattle Police,” an authoritative voice crackled

through a loudspeaker. The rest was drowned out by the loud discharge from a

grenade launcher and the disarming hiss of tear gas, punctuated by the shots of

rubber bullets. Suddenly, we were scrambling, coughing, gasping, and crying. The

police advanced, flanked by an armored personnel carrier. Yet, just as quickly

as we dispersed, we returned – this time with bandannas on our faces and water

for our eyes. We weren’t going to be moved so easily. And again, the face-off

began. Such was the rhythm of the day.

Alone, this scene was inspiring. But what was truly remarkable was

that we at that particular intersection were not alone. For blocks around us –

stretching out of view and snaking around buildings – were thousands more

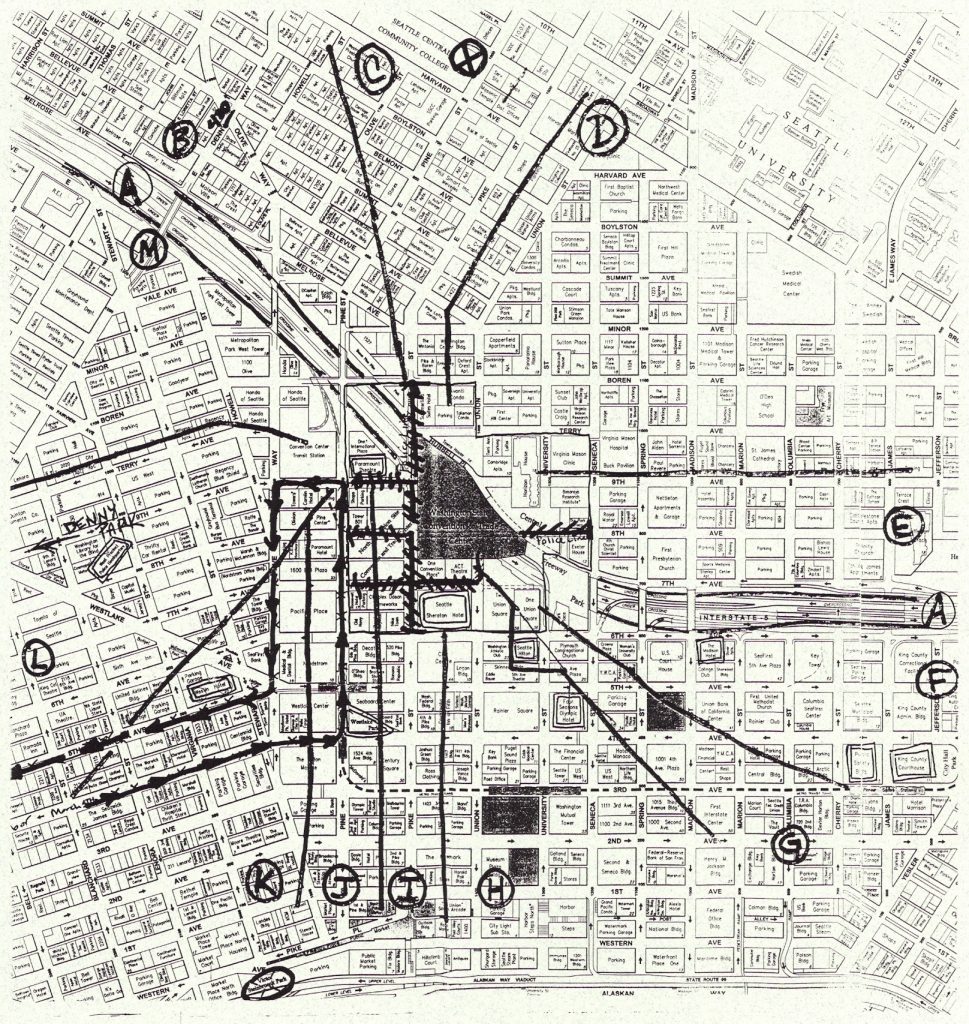

people. There were blockades at every single intersection in the twenty blocks surrounding

the Washington State Trade and Convention Center. In addition, many local students

and workers were on strike that day, and the International Longshore and

Warehouse Union had shut down the ports along the entire West Coast.

Who could have guessed that this was going to happen? Even those of

us who had spent months planning to “shut it down” were stunned when our

rhetoric became reality. On that Tuesday, the first day of WTO Ministerial

meetings ever to take place in the U.S., most sessions were canceled because our

blockades were so effective. The Seattle

Times quoted one of the last WTO delegates to leave that afternoon: “That’s

one for the bad guys.” We were the bad guys, and we clearly won.

In the years since, “Seattle 1999” has become a shorthand. People

have produced articles, books, graphic art, music, documentaries,

at least one oral

history project, and even a Hollywood

film about the protests. Police agencies and security analysts have closely

studied “the battle of Seattle” in order to thwart similar efforts. Left

intellectuals have used the Seattle protest experience to advance all sorts of

theories about radical politics. The so-called “Seattle riots” have become an

historical reference point for journalists covering U.S. protests. Not

surprisingly, much is missing in these accounts.

With the twentieth anniversary of the Seattle protests, now is a

good time to revisit the history from the perspective of those who were deeply involved in organizing the mass

direct action. I was one among them – at that time, a 22-year-old activist

living in Olympia, Washington. Along with dozens of others, I co-founded the

Direct Action Network in the summer of 1999 and spent months organizing for the

WTO shutdown. In what follows, I draw on accounts from other organizers and my

own experiences to discuss the lead-up to Seattle, what actually happened, and

what we can learn from it, all with an eye toward our current circumstances of

struggle in North America.

Not the Beginning

Before the tear gas had even cleared in Seattle, the mainstream

media had pronounced the birth of the so-called “anti-globalization movement.”

However, as experienced activists emphasized right away, Seattle was not the beginning. A worldwide revolt against

neoliberalism had been growing for nearly two decades, and U.S. activists from

a variety of social movements had targeted international financial institutions

and trade agreements since the early 1990s. The road to Seattle was paved with

years of organizing, confrontational struggle, and cross-border

movement-building.

This started in the

mid-1980s in the Global South, especially Africa and Latin America, with increasingly

widespread struggles against austerity measures mandated by the

International Monetary Fund (IMF). Building on legacies of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements, these mobilizations

particularly fought IMF-imposed price hikes and cuts to social spending. And by the early 1990s, meetings of neoliberal institutions such as the

World Bank and the WTO faced massive protests from Bangalore to Berlin.

Meanwhile, a convergence of movements was developing in the U.S. The

labor movement, longstanding international solidarity efforts, Indigenous

groups, the environmental movement, consumer advocacy and human rights

organizations, and others took increasing aim at so-called “free trade”

agreements. They argued that these agreements strengthened corporate power, undermined

Indigenous sovereignty, slashed protections for workers and the environment,

and degraded standards of living. During the early 1990s, many activists found

common cause in the fight against the North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA). Although ultimately unsuccessful, that struggle forged important

cross-movement and cross-border relationships.

On January 1, 1994, the day that NAFTA went into effect, the

Zapatista Army of National Liberation emerged on the world stage by seizing

seven cities in Chiapas, Mexico. “Ya

Basta!” (“Enough!”), they said in opposition to the Mexican government and

neoliberalism. Bringing together aspects of left radicalism and Indigenous

Mayan traditions, the Zapatistas offered an autonomous anti-capitalist politics

that inspired movements across the globe. The Zapatistas also actively

facilitated transnational links among movements. Starting in 1996, they

sponsored face-to-face global Encuentros (Encounters) that served

as key meeting points for what later became known as the global justice or

alter-globalization movement.

The initial Encuentros led

to the formation of the Peoples’

Global Action (PGA) network in 1998. The PGA brought together massive

movements in the Global South, such as the Landless Workers’ Movement in Brazil

and the Karnataka State Farmer’s Movement in India, along with generally

smaller organizations in the North, to develop horizontal links in the struggle

against neoliberalism. This network was a key node through which an emerging

anti-capitalist current in the global justice movement was able to engage in

discussion and planning. The PGA Hallmarks,

developed through early conferences, came to define this anti-capitalism. They

included a rejection of “all forms and systems of domination and

discrimination,” “a confrontational attitude,” “a call to direct action,” and

“an organisational philosophy based on decentralisation and autonomy.”

By the late 1990s, actions and campaigns against what was increasingly

called “corporate globalization” were kicking off all over the U.S. Activists

targeted the IMF and World Bank, and engaged in a sustained fight against the

Multilateral Agreement on Investment. Anti-sweatshop campaigns blossomed on

university campuses, activists identified and challenged government policies

that facilitated corporate power, and environmental and labor groups built

coalitions to take on companies responsible for ecological destruction and

worker exploitation. And increasingly, this ferment bubbled into

confrontational collective action. A direct antecedent for Seattle was the wave

of protests in Vancouver in 1997 that confronted the summit of the Asia-Pacific

Economic Cooperation (APEC), a regional trade agreement among a number of

Pacific Rim economies.

While activists from a range of political orientations participated

in these activities, anarchism animated the dynamic anti-capitalist current.

This was an anarchism that combined a far-reaching critique of domination with a commitment to direct

action and direct democracy. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, anarchists had

participated in and learned from the experiences of a succession of

direct-action movements, especially the radical wing of the anti-nuclear

movement, direct action AIDS organizing, and radical environmentalism. Building

on these experiences, they synthesized a set of protest tactics and organizing

practices that became widely influential in the global justice movement. Movement

journalist L.A. Kauffman aptly describes this

as a multi-decade process of “radical renewal.” And as she emphasizes, it was

queer women activists, “both white and of color, who most often formed the

bridge between one movement and the next, transmitting skills, insight, and

expertise.”

Anarchist-influenced activists were deeply inspired by the

Zapatistas and had been some of the first to work with the PGA. Following the

example of their European counterparts, many began organizing around the PGA’s

calls for “global

days of action” involving coordinated international protests against

institutions of neoliberalism. At its second annual conference in Banglore, India, in August of 1999,

PGA endorsed global actions in solidarity with the protests in Seattle on November

30.

Many Organizing Efforts

In early 1999, Seattle was announced

as the choice for the WTO’s “Millennium Round.” Within a month, word was

rapidly spreading through West Coast activist circles. Many pointed to it as an

unprecedented opportunity for protest since the Seattle Ministerial would be

the first international trade meeting of its kind to be held in the U.S. Some

of us had been at the Vancouver anti-APEC actions in 1997 and, with Seattle, we

saw the possibility of the APEC protests multiplied by one hundred.

Effective protests are rarely

planned overnight. Rather, they come out of patient, dedicated, and frequently

frustrating organizing efforts. Seattle was no different. Every effort faced an

exhausting array of concerns, debates, and planning sessions. How can we build

strong coalitions? How can we get the word out? How can we effectively protest

the WTO? How can we make sure that our phones get answered? These and many more

pressing questions were on the agendas of countless meetings.

The organizing efforts for Seattle developed

along several different lines and were never fully unified. In fact, there were

some significantly divergent initiatives. One was the People for Fair

Trade/Network Opposed to the WTO (PFFT), initiated in the spring of 1999.

Launched with the assistance of the national organization Public Citizen, PFFT

drew together a broad umbrella of consumer advocacy groups, environmentalists, human

rights activists, and others. PFFT set the stage for much of what went down in

the faith communities, on the college campuses, in the educational forums, and

on the evening news in Seattle.

Filipino anti-imperialist networks

also played a key role. Radical groups in the Philippines with strong

international ties organized mass protests against the 1996 APEC summit in

Manila. Associated organizations in Vancouver, particularly the Philippine

Women’s Center, carried

this momentum into a counter-conference and protests against the 1997 APEC

summit. In early 1999, with support from experienced Vancouver activists, Sentenaryo ng Bayan, a Filipino community organization

in Seattle, began organizing the NO to WTO/Seattle International People’s

Assembly. This two-day assembly brought together delegates from twelve

countries and culminated in a major march on November 30. The People’s Assembly

effort, perhaps more than any other, mobilized racialized communities in

Seattle alongside movements in the Global South.

The labor movement generated a lot

of energy as well. Starting in the summer of 1999 and building through the fall,

the AFL-CIO devoted substantial resources to Seattle efforts, widely

circulating educational materials and mobilizing intensively through labor

councils and union locals. There were clear tensions within the labor movement,

however, as national union leaders proclaimed their demand “to have a place at

the table” while more radical unions, independent labor formations, and some rank-and-file

members took more critical stances. Ultimately, the labor movement mobilized

the largest numbers, bringing some 30,000 people to the streets on November 30.

There were also some unlikely

alliances that laid the groundwork for Seattle. At the grassroots level, one of

the most pivotal was between unionized steelworkers and Earth First! The

steelworkers, who worked at five plants in three states, were involved in a

protracted fight with their employer, Kaiser Aluminum, which had locked them

out in early 1999. Kaiser, as it turned out, was owned by Maxxam and headed by

infamous CEO Charles Hurwitz,

who also owned Pacific Lumber, the company clear-cutting old growth redwood

forests in northern California. Earth First! had been involved in direct-action

efforts to protect those forests since the 1980s. Identifying their common

enemy, the locked-out steelworkers and the forest defenders began collaborating

on protests and spending time together on picket lines and in tree-sits,

especially on the West Coast. These relationships, which eventually formalized

in Alliance for Sustainable Jobs and the Environment, were crucial in the direct-action

organizing for Seattle and in the streets during the protests.

Planning and Training

The vision for mass direct action in

Seattle developed through an informal network of West Coast radicals. Many were

connected to Art and Revolution collectives and associated groups, which were

known for injecting graphics, theater, and songs into activism. Beginning in

June of 1999, this network started holding conference calls and email discussions

with groups from Los Angeles to Vancouver. Some of those involved initiated a

face-to-face meeting in Seattle in mid-July with people from several northwestern

cities. In August, these overlapping efforts merged, and we decided to call

ourselves the Direct Action Network (Against Corporate Globalization).

DAN started out as a loose

conglomeration of primarily anti-war activists, anarchists, direct-action environmentalists,

anti-prison activists, international solidarity groups, and unaffiliated

radicals. We eventually evolved into a more structured coalition, bringing

together organizations such as the National Lawyers Guild, Rainforest Action

Network, Industrial Workers of the World, Mexico Solidarity Network, War

Resisters League, and Seattle Earth First!. We were predominantly white and

mostly young.

Over the course of months of

meetings, DAN developed a plan for mass direct action on November 30. This

would be an action, as we wrote, “involving hundreds of people risking arrest

and reflecting the diversity of groups and communities affected by the World

Trade Organization and corporate globalization.” Our aim was “to physically and

creatively shut down the WTO.” We weren’t interested in routine and largely

symbolic arrests; as much as possible, we wanted to prevent the Ministerial

meetings from happening.

Organizers with significant

experience from the direct action anti-nuclear movement played leading roles in

shaping DAN’s approach. As a result, the core features of our action plan were adopted from that movement.

One – which was controversial in planning discussions and became even more so

later – was a set of “action guidelines” to which all participants were asked

to agree: no violence, no weapons, no use of alcohol or illegal drugs, and no

destruction of property.

Another feature was affinity groups: DAN asked participants to form self-reliant

groups of five to fifteen people each who would

determine their own creative plans for physically blockading intersections

around the WTO meeting. Each affinity group designated a spokesperson who

coordinated with others in “spokescouncil” meetings and then reported back to

their fellow members. Many affinity groups also agreed to work with each other

in “clusters” which took responsibility for particular intersections. Some

clusters shouldered particularly ambitious projects. For instance, the cluster

known as the “Flaming Dildos” volunteered to shut down the area next to the

interstate highway running underneath the Convention Center.

The other core feature was jail solidarity: DAN encouraged participants to be

prepared, if jailed, to act collectively to protect each other and carry on

direct action. This strategy was based

on the assumption that large numbers of activists would be arrested on November

30. With this expectation, DAN recommended that arrestees use noncooperation

tactics to get equal treatment and charges lowered or dropped for everyone.

Chief among these tactics was arrestees refusing to give names when being

processed. If need be, hundreds of jailed activists could also refuse to move

or comply with other orders, clogging the legal system with their efforts. As part of this, DAN arranged to

have substantial legal support – including a staffed office and lawyers –

available for arrested activists.

To spread the word about our plan, DAN

developed and distributed more than 50,000 copies of a broadsheet with

information about the WTO and details about participating in the direct action.

DAN also organized a roadshow that toured along the West Coast, offering

performances and action trainings. DAN members regularly facilitated popular

education workshops and spoke at events throughout the region. And just before

the WTO meetings began, DAN ran a nine-day “Direct

Action and Street Theater Convergence” in Seattle, where we offered regular orientation, trainings, meals,

and space for protest preparation. The convergence

also provided a time and a space for people to develop artwork of all kinds –

from giant puppets to block-printed banners to dance and theater performances –

for the streets.

Training was central to DAN’s action plan. We prioritized preparation and skills-building in all of what we did in the lead up to the protests. We regularly offered trainings in nonviolent direct action, jail solidarity, first aid, blockade tactics, meeting facilitation, street theater, and more. Most trainings lasted hours and included in-depth role-plays. Emphasizing the importance of these trainings, Seattle DAN organizer Jennifer Whitney would later recount:

Thousands of people went into the action on November 30th having already practiced how they would set up their blockade, what they would do when police came, how they would respond to tear gas or pepper spray, how they would behave during arrest, transport, booking, etc. It really demystified the process for people who had never been arrested before; for them, it was a revelation not only to have the entire scenario spelled out step-by-step, but actually to be ‘arrested’ by activists in cop costumes, and to act out the entire process, including interrogation scenes where the ‘cops’ used different lies and manipulations to try to extract information. Trainings built confidence as well, not only in ourselves but in our community. The knowledge that hundreds of people would be on the street to give you first aid if you were hurt, and to observe and document any police action against you, and to track you through the jail and court system, inspired people to push their limits, to test their endurance, to imagine what was possible and then go one step further.

Not everyone who protested in

Seattle came through DAN. But we trained thousands of people and reached tens

of thousands more with our plans. Our efforts created an infrastructure for

what unfolded in the streets.

What Actually Happened?

By October 1999, there was a palpable buzz about the upcoming

protests. People across North America were making travel arrangements to get to

Seattle, and we heard about more and more union locals, student organizations,

and community groups organizing buses. Those of us involved in planning the DAN

convergence put out a call for pre-registration and we were startled to receive

responses from people coming from far outside the U.S. In Olympia, a hub city

for DAN, our planning meetings that initially involved 15-20 people were

regularly bringing out more than 100. The same was happening in many other cities.

On November 20, we opened the DAN convergence center – a spacious

former dance club with an industrial-sized kitchen – at 420 East Denny Way near

downtown Seattle. Almost immediately, out-of-town activists began streaming in,

more and more every day. Convergence space organizers hustled to orient and

care for this influx of people, maintain and update an increasingly packed

schedule of meetings and trainings, mediate conflicts as stress grew, and deal

with corporate journalists.

The convergence also provided a space for funneling

out-of-town activists into local resistance to the WTO, which was building in

intensity. Starting on November 21 with a festive neighborhood procession,

Seattle saw almost daily protests and other visible actions. For example, the

following day, corporate watchdog Global Exchange brought a few hundred

protesters to the heart of downtown to demonstrate against the use of sweatshop

labor by the Gap. As marchers reached Gap subsidiary Old Navy, two climbers

rappelled off of the roof, unfurling a banner which read, “SWEATSHOPS: ‘FREE

TRADE’ OR CORPORATE SLAVERY?”

On November 24, the PGA caravan arrived. The busload of

activists from across the world had departed from the U.S. East Coast in late

October. Along the way to Seattle, they stopped in over twenty cities, “trying

to communicate the impacts of globalization on our communities,” in the words

of Indian participant Sanjay Mangala Gopal. They brought tremendous enthusiasm

for the coming protests and tangibly demonstrated the PGA’s support.

By November 27, two days before the Ministerial, the

tally of actions was mounting. In the middle of the night, activists had placed

a fake front page on 25,000 issues of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer,

satirizing its coverage of the WTO. A rally on the University of Washington

campus had marched the full length of a main avenue, occupying key

intersections with guerrilla theater. A large, multi-gender squad of “radical

cheerleaders” dressed in red mini-skirts had crashed the annual Bon Marche

parade through downtown Seattle. A critical mass bike ride of 400 people had

ridden down main streets and eventually opened the doors of the Convention

Center, riding straight through. Two activists had scaled a retaining wall next

to Interstate-5 with a “SHUT DOWN THE WTO” banner while one of their mothers shouted words of encouragement.

November 28 was the first day of the International People’s Assembly at the Filipino

Community Center. With significant representation from the Global South, more

than 200 delegates participated in this two-day series of presentations and discussions critically analyzing the WTO as an instrument of

imperialism. In its concluding session, the People’s Assembly produced a unity statement, which, in part, declared their collective commitment

“to confront the imperialist monster that has taken away our lands, jobs and

livelihood and has further displaced, commodified and turned women into

modern-day slaves.”

At the same time, over 1,000 people paraded through

Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood in the largest procession yet. The

steelworkers who led the march carried colorful, hand-painted pictures of

snakes overlaid by the words “DON’T TRADE ON ME.” Later in the day, several

hundred of us went downtown for an impromptu protest at the Gap. Led by a white

van blasting techno music and frequent interludes about the wages of Gap

sweatshop workers, we managed to occupy a major shopping area.

November 28 also saw the opening of the Independent

Media Center (IMC) at 1415 Third Avenue in downtown Seattle. Formed by a small crew of activists and

housed in a space donated temporarily by a local nonprofit, the IMC functioned

as a hub for movement media-making during the protests. The IMC issued 450 of

their own press passes, distributed 100 camcorders to street-based

videographers, printed and distributed a small daily newspaper, and provided a physical

space with phone lines and reliable high-speed internet for hundreds of

activist journalists. Perhaps most significantly, the IMC also set up a website that enabled people to upload audio, video, photos,

and text in real time to a newswire; in the era before social media, this opened up unprecedented space for participatory activist journalism. As the protests unfolded, the

IMC quickly became the most reliable source of information.

N29: A Beginning

Monday, November 29 was the unofficial beginning to

the WTO Ministerial, although no actual meetings occurred. Starting on this

day, the number of resistance activities throughout the city began to ramp up

exponentially – with multiple protests, direct actions, and educational events happening

simultaneously for the next several days.

On that morning, we learned that dozens of squatters

had occupied an abandoned building near the downtown police station. They were

able to hold the building until the end of the WTO meetings. Meanwhile, Seattle

commuters started their work week in sight of five members of the Rainforest

Action Network dangling from a 170-foot crane with an enormous banner which

read “Democracy” and “WTO” with arrows pointing in opposite directions.

In the streets, more than 200 animal rights activists

and environmentalists costumed themselves as sea turtles (protected under the U.S.

Endangered Species Act, which the WTO was threatening). Originally part of a

Sierra Club march, they and some 2,000 others roamed downtown, eventually

stopping to join French farmer José Bové in a protest at McDonalds. At the

time, Bové was something of a movement celebrity, famous for bulldozing a

McDonalds under construction in France.

The day ended with a “human chain to end Third World debt.”

Led by an interfaith coalition, nearly 5,000 people marched to encircle the

site of the WTO’s opening gala seven times over. They called for the powerful

member nations of the WTO to cancel the debt of the world’s poorest countries.

In the pouring rain, they chanted, “We’re all wet, cancel the debt!”

N30: “Shut It Down!”

Tuesday, November 30 – known internationally as “N30”

– was the day we had been building toward for months. As I walked to downtown before

dawn with my affinity group, actions were already underway. Workers were

calling in sick, students were skipping school, cab drivers were engaged in a

work stoppage, and longshore workers had shut down all of the West Coast ports.

Police cars were present on every block and the cops

were vigilantly watching us. I saw two people pushing a shopping cart with a

puppet and U-locks who were suddenly surrounded by police officers. When asked,

the police declared that the pair would not identify themselves or admit that

the shopping cart was theirs. After enough of a crowd grew to observe, they

were released – minus the shopping cart. On the other side of downtown, two

activists carrying pieces of a tripod, a large teepee-like structure for

blocking roads, were detained by police and eventually arrested. Separately,

both were interrogated, one pepper-sprayed and the other strapped to a chair

and threatened with rape. Later, they were released with no charges.

DAN had announced two public meeting locations on opposite

sides of downtown. Protesters gathering at both sites grew from the hundreds to

the thousands by 7:30am when they began lively processions toward downtown. It

was an astonishing sight. Looking around, there was a group of activist Santa

Clauses, many returning sea turtles, a sprinkling of stilt-walkers, a jubilant

squad of radical cheerleaders, a vast number of giant puppets, an anarchist

marching band with matching pink gas masks, and thousands of ordinary people

who looked very determined.

As the processions neared police lines around the

Convention Center, some affinity groups deployed blockades; others were already

in progress. By the time marchers had circled the nearly twenty-block

circumference, protesters had blocked every single intersection, alleyway, and

hotel entrance. Some simply sat across roads with arms linked. Others locked

their arms inside pipes known as “lockboxes,” creating human walls. Still

others used a combination of U-locks and bike cables to chain their necks

together. One affinity group successfully set up a tripod with a protester

sitting at the top and others locked to the base.

Confronted with these human blockades and thousands of

their supporters, the police were visibly tense. Interestingly, President Bill

Clinton had canceled his welcome address a few days before – perhaps

anticipating its failure. The official opening of the WTO Ministerial was still

scheduled for delegates. Yet, as mid-morning approached, they were unable to

make it into the Convention Center. While some stopped to speak with protesters,

others simply tried to push their way through.

By 10am, the police were preparing to create a

corridor for “safe entry.” They choose an intersection with a less fortified

blockade, gave a quick warning, lobbed in tear gas canisters, and shot a volley

of rubber bullets. The few protesters who remained were arrested, many of them

pepper-sprayed in the process. At a few other intersections, police beat

activists with two-foot long batons to try to force them to move.

Despite police efforts, the WTO meetings were

effectively shut down. Indeed, as Assistant Police Chief Ed Joiner would later

flatly admit, “The police strategy failed.” Word quickly made its way through

the crowds that the morning session had been canceled and that the only people

inside the Convention Center were the press. The Seattle Times would later

report that, throughout Tuesday morning, “US Secretary of State Madeleine

Albright and US Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky were holed up in the

Westin Hotel. Federal law-enforcement officials said the streets of Seattle

were too dangerous for them to travel the few blocks to the opening

ceremonies.”

Meanwhile, the People’s Assembly

march was heading toward downtown, growing to some 2,000 people along the way. Ace

Saturay, who coordinated the march,

later explained, “We made the strategic decision to start the [march] in the

International District, a low-income community of color, with a large

population of immigrants…that is experiencing the domestic impacts of

institutions like the WTO policy thrusts.” They did this in open defiance of

the City of Seattle; of the numerous groups to apply for march permits, only

the People’s Assembly was denied.

By late morning, crowds of protesters around the

Conference Center downtown swelled with the arrival of the People’s Assembly

and student walkout marches from nearby colleges and high schools. Some 10,000

people surrounded the Convention Center.

Although police continued to shoot tear gas and rubber

bullets, most locked-down activists began to relax. Some people, such as

Portland DAN organizer Nancy Haque, unlocked from their blockades to look at

was happening in other areas around the Convention Center. When I ran into her,

she summarized the scene with a smile, saying: “We own the streets of Seattle.”

This was no exaggeration. In every direction around us, the streets were full

of jubilant protestors and the prevailing mood was festive. Some were dancing,

others were engaged in enthusiastic conversations, and many were simply looking

around with complete awe. A few people were decorating buildings with graffiti,

and others pushed dumpsters and newspaper boxes into intersections to reinforce

existing blockades.

While we were holding intersections, some 30,000 union

members were gathering for a labor rally and march at Memorial Stadium,

adjacent to downtown. In the early afternoon, they headed down Pine Street, in

sight of many of the blockades. Faced with the mass direct action, labor’s

unity dissolved. While AFL-CIO marshals directed many marchers away from the

blockades, some trade unionists rushed through the marshals to join the

thousands of protestors already occupying the streets.

As the day drew on, confrontation between police and

protesters intensified once again. Those of us near major blockades became more

accustomed to tear gas, and some protesters began throwing canisters back. Some

activists set the contents of an overturned dumpster on fire. Meanwhile, office

workers and shoppers scrambled to get past the looming clouds of tear gas, many

of them pausing to have their eyes flushed by DAN medics. Throughout, crowds

frequently chanted “Nonviolence!” or displayed the two-fingered peace symbol.

By this point, it was becoming plainly evident that some

of the DAN action agreements – specifically, against property destruction – had

begun to unravel. Even when we had first developed the agreements, there had

been debate about whether we should or could ask people to abide by them.

Clearly, some people in the streets had not agreed to them.

Since mid-morning, a well-organized contingent of a

few hundred black-clad and masked people had been shattering windows at

corporate targets, including Nike, the Gap, and Bank of America, and slashing

tires of limousines and police cars. Using a black bloc formation – at that

point, very novel in the U.S. – they stuck together, protected one another, and

avoided confrontations with police. One black bloc collective later circulated

a communiqué explaining why

they targeted specific corporations for property destruction. “When we smash a

window,” they wrote, “we aim to destroy the thin veneer of legitimacy that

surrounds private property rights. At the same time, we exorcise that set of

violent and destructive social relationships which has been imbued in almost

everything around us.”

Many media reports at the time (and since) described Seattle

as completely devastated by the black bloc. In reality, mainly corporate stores

in the heart of downtown were damaged. Still, these actions sparked intense

controversy in the following days. Labor leaders and other prominent organizers

denounced the black bloc, as did some protestors. Others warned of the dangers

of equating minor damage to buildings with the pervasive police violence. Still

other activists questioned the property destruction not so much on

philosophical grounds but tactically. There was no consensus and, if anything,

the debate grew more intense with summit protests in subsequent years.

Back on the streets, the police were clearly agitated.

As the afternoon turned into evening, rumor spread that Seattle Mayor Paul

Schell had declared martial law. In fact, he had declared a “civil emergency”

and set a curfew for 7pm to 7:30am in the downtown area. Many activists who

were still locked down began to discuss leaving as they realized that they

could come back for another day of blockades on Wednesday.

Just as the largest blockade was preparing to leave,

the police opened fire with tear gas and rubber bullets. They added a new

weapon too: concussion grenades, small projectiles that hit the ground with a

bright, booming explosion. In the face of this attack and pursuit by the

police, protesters splintered, many hastily heading out of downtown. The police

hounded the remaining crowds of protesters into the nearby Capitol Hill

neighborhood. There, residents and activists alike were tear-gassed and

pepper-sprayed by police through several hours of repeated standoffs and

assaults.

By the end of Tuesday, 68 people were in jail and many

others had suffered from police violence. The DAN convergence center was turned

into an emergency clinic for protesters with severe pepper spray burns and

dangerous cases of tear gas inhalation.

D1: Crackdown

The morning of Wednesday, December 1, saw protesters

marching downtown once again. This time, police quickly intercepted them. While

some held their ground and were arrested, others continued to march,

outflanking police for over an hour as their numbers grew into the hundreds. When

the march stopped at Westlake Park, police surrounded them and separated people

into those who wanted to be arrested and those who didn’t. Then, all of them –

“arrestables” and “non-arrestables” alike, including members of the DAN legal

team – were arrested and dragged onto buses. A crowd of hundreds loudly

supported them from behind police lines.

Under Seattle Mayor Paul Schell’s orders, the police had

cordoned off a massive section of downtown with the Convention Center in the

middle. They were assisted by some 200 National Guard troops. Entering that

area without a “legitimate reason” (i.e., being a WTO delegate, cop, resident,

or office worker) became punishable by fines and jail time. Schell was

attempting to create a “protest-free zone.”

The full weight of Schell’s declarations wasn’t fully

apparent until later in the afternoon. As police turned countless protesters

away from downtown, some 2,000 gathered outside of the protest-free zone for a

short march and rally with the steelworkers. Most of us assumed that as long as

we stayed with the unions, we wouldn’t be attacked by the police. We still held

onto that hope as we joined more militant trade unionists in a march from the

rally site toward downtown.

As we approached the no protest zone, police suddenly

assaulted us with tear gas and concussion grenades. The march scattered into

several large groups and many people sustained injuries. One person went into

shock; another person passed out, landing on her face and fracturing her jaw,

after a canister exploded at her feet; and one older person was hit in the face

with a rubber bullet and temporarily blinded in one eye. The lines between

protesters and downtown shoppers blurred as everyone tried to escape. Relentlessly,

police chased the scattered groups of protesters. At Pike Place Market, some

activists sat down to try to de-escalate the situation. Police reacted by

pepper-spraying medics, shoppers, and marchers alike.

As some people sought medical attention, others simply

fled. In the distance, more riot police amassed. A couple of hours later, these

would be the police who chased a remaining splinter of nearly 300 protesters

away from the protest-free zone, assuring them that they could continue their

march if they went North – only to be corralled by armored police vehicles. The

police proceeded to throw in tear gas and command everyone to “get on the

ground” or else face more gas. Then, over two-thirds were arrested – the

remainder spared because the police ran out of buses to transport arrestees.

On the other side of town, at Sand Point Naval Base,

seven busloads of arrested protesters refused to get off to be processed. Going

for over thirteen hours without food, water, or bathroom facilities, they

demanded to see DAN lawyers. By the middle of the night, they had all been

dragged off, some pepper-sprayed. Activist Jamie Taylor would later tell how

most remained undaunted, singing as they had learned in legal trainings: “I am

going to remain silent/uh-huh, uh-huh, uh-huh/I want to see a lawyer/oh yeah,

oh yeah, oh yeah.” Once in processing, the majority of them refused to give

their names, so they were issued wristbands with either “Jane WTO” or “John

WTO” followed by a number.

Over the following days, police and guards ruthlessly

terrorized jailed activists who tried to maintain solidarity. A significant

number of arrestees were strip-searched, pepper-sprayed, or otherwise

brutalized, and most had inadequate access to food and clothing. Still,

solidarity sometimes prevailed. At one point in jail, guards came to Nancy Haque’s

cell to separate her from others. She later recalled, “when I didn’t

immediately comply I was threatened with solitary confinement. My cell mates

responded by locking their arms around me, singing ‘Si, se puede’ (‘Yes, we

can’). The jail officials let me stay.”

Outside, for the second night in a row, police pursued

protesters into Capitol Hill. Helicopters with searchlights circled overhead

while sirens screamed late into the night, punctuated by the regular sound of

tear gas shots. This time, residents were even more furious at the

military-like invasion, shouting at police to leave their neighborhood.

By the close of the day, the score was clear: if we

had won on Tuesday, the police had won on Wednesday. However, they were losing

in the eyes of Seattle residents. As I walked out of downtown that evening,

people were gathered in bars and cafes watching live footage of police firing

tear gas and rubber bullets into protesters. I overheard downtown office workers

speaking angrily about Schell’s declarations. Meanwhile, many shopkeepers had

put up supportive signs in their windows, such as “WTO, GO HOME” or “We support

peaceful protesters.”

D2: “This Is What Democracy Looks Like!”

On the morning of Thursday, December 2, hundreds of activists

amassed on Capitol Hill and marched toward downtown. It was, by far, the most

colorful procession since Tuesday morning. Marchers carried signs, flags,

banners, towering skeleton puppets, and a giant papier-mâché human head flanked

by two large hands connected with painted banner-sleeves. Like many of the

protesters, the head was gagged in order to visually communicate the effects of

Mayor Schell’s declarations. Offering further comment, one marcher’s sign read:

“THIS IS A FREE PROTEST ZONE.”

As I caught up with the march, a song wafted through

the crowd: “We have come too far/We won’t turn around/We’ll flood the streets

with justice/We are freedom bound.” In counterpoint, others chanted, “This is

what democracy looks like!” Together, the song and chant reinforced our

collective sense of power. More and more people joined our procession.

Following a brief downtown rally, marchers amicably split

into two processions – one heading to protest multinational agribusiness

company Cargill and the other toward major WTO sponsor and timber corporation

Weyerhaeuser. The vast majority – upwards of 2,000 – followed the latter,

briefly stopping at Weyerhaeuser’s Seattle headquarters to hang banners and

then moving to the county jail, where many of the nearly 500 arrested

protesters were being held.

As we arrived, police blocked off the nearby freeway

entrance, clearly fearing that we would occupy the interstate. Our focus,

however, was on the people inside. A protestor held a hand-written cardboard

sign: “FREE THE SEATTLE 500, JAIL THE FORTUNE 500.” Marching around, we could

see prisoners pressed up against cell windows and raising fists. Activist Hank

Tallman, in jail at the time, later told how, on his one phone call, the DAN

legal team had mentioned the 2,000 outside. “I turned to the rest of the

prisoners in the cell block and yelled,” he said. “They were all cheering.”

Outside, we held hands to encircle the building.

Others gathered near the front and we soon heard that an affinity group had

physically blockaded the main entrance. Tension was mounting, with many of us

preparing for tear gas, but the police maintained only a light presence. Within

an hour, the blockading affinity group announced their demands: unconditional

freedom for all nonviolent protesters and a public apology from the city of

Seattle. Those of us who were willing to risk arrest began joining the others

at the entrance, overflowing into the sidewalk and onto the street. Still, the

police stuck to the periphery. We appeared to be in a protracted standoff, and

patiently we waited.

As the sun set, a representative from the DAN legal

team announced that they had been negotiating with city officials who had

granted a concession: if we ended the blockade, officials would allow pairs of DAN

legal support workers to consult with groups of jailed protesters. Many present

grumbled, saying that the city was only allowing prisoners the rights already

owed to them. The affinity group that had sparked the action, however, urged us

to exit the blockade with them. Slowly, we began to march home.

D3: Success

By Friday, December 3, most of us were dragging. After

a week of running from riot police, inhaling tear gas, and enduring constant

sleep deprivation, many were looking for a sense of closure as well as more

news about the 500 still in jail.

As a final mass action for the week, the County Labor

Council organized a rally and march from the local labor temple. Altogether,

several thousand people wound their way through downtown with shouts of

encouragement from construction workers, motorists, and other passersby. At the

conclusion of the march, a large group of protesters –including many previously

uninvolved Seattle residents who were outraged about Mayor Schell’s

declarations – turned back toward downtown. As our spontaneous march approached

police lines, protesters argued about whether we should focus on the WTO or

those who were in jail. In the end, the march broke in half: one group went to

the jail and another remained in sight of the Convention Center.

Once at the jail, several hundred gathered to sort out

what we could do for those inside. To chants of “let them go!” the DAN legal

team reported that many arrestees were being brutalized and isolated, and some

weren’t getting necessary food and medical treatment.

The rest of the day was an astonishing exercise in

direct democracy. With skillful facilitation from a volunteer in the crowd, the

hundreds present deliberated about how to proceed. Twenty-three people

presented proposals for how best we could force the city to negotiate with our

legal team, and then we split into impromptu affinity groups to discuss the

proposals. Each group reached a consensus on what it favored and then sent a

spokesperson to hammer it out with some 20 other spokespeople. Within two

hours, we had a detailed action plan to occupy the entrance of the jail until

all the protesters were released. We then began making preparations for a long

stay.

While we were making our decisions at the jail, the

other half of our march had chosen to blockade the Westin Hotel, where many WTO

delegates were staying. An affinity group of eight people U-locked themselves

to the main entrances while hundreds of others occupied the road and sidewalk

in front.

As both groups hunkered down, news leaked from the

Convention Center that the WTO Ministerial had ended with no agreement on a new

round of meetings. Earlier that morning, the African delegation had booed the U.S.

Trade Representative as she walked into a plenary session. And as the day came

to a close, a coalition of delegates from over 70 countries in Africa, Latin

America, and Asia had stubbornly refused to sign onto an agenda in which they

saw they had little voice. The WTO wasn’t dead, but it was severely stalled.

The next day, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s bold headline read,

“Summit ends in failure.” Our efforts had contributed, some delegates would

later admit, by costing the Ministerial nearly two full days of meeting time.

With the word of success, occupations at the jail and

the Westin turned into street parties with dancing, drumming, and singing late

into the night. The commitment of protesters was only buoyed by the news. At

least one hundred stayed in each location overnight. Those at the Westin

finally decided to unlock the next morning. The occupation of the jail would

continue for days, until most of the arrested protesters were released on

Sunday, December 5. We would later learn that, alongside our solidarity tactics

in and outside the jail, some trade union leaders put intense pressure on the City of

Seattle to release those arrested.

Legacies and

Lessons

Toward the end of that week, we began chanting, “WTO,

you’ve gotta go!/The people came and stole the show!” This was apt. As many commentators

would later point out, thousands of us went up against one of the most powerful

organizations in the world – and we won.

Our victory is an enduring legacy of the Seattle

protests. Through direct action and direct democracy, thousands of ordinary

people – students, workers, parents, community organizers, activists, and many

others – made history. Those of us who organized for the shutdown were

consciously audacious in our politics and our strategy, and this created space

for an astonishing upsurge with effects we could not have anticipated.

Ultimately, we contributed to fundamentally shifting public discussions about globalization and inequality.

Just as important was our internationalism, what we

called “globalization from below.” We saw ourselves as participating in a

struggle that was global, and we paid careful attention to movements in other

parts of the world, particularly the Global South, that had been fighting

mightily against neoliberalism. Many of us were involved in international

solidarity efforts, and we understood that we had particular responsibilities

as people organizing in the U.S. Through our victory in Seattle, we

unequivocally communicated to people across the globe that there are many in

the U.S. struggling against the rule of profit and, to use a Zapatista phrase, fighting

for “a world in which many worlds fit.”

Alongside these legacies, there are also valuable

lessons to take from our experience in 1999. I’ll name two here. The first is

that what we do is never perfect; the point is to learn from our mistakes,

build on our successes, and work to do better. In the case of Seattle, our organizing had some significant flaws. As Olympia DAN organizer

Stephanie Guilloud observed, “We were not building a long-term resistance

movement: we were mobilizing for a protest.” And as we urgently mobilized, many

of us sidestepped the political implications of the fact that we were

predominantly white.

Privilege framed white organizers’ experiences in many ways. We mostly stayed within our customary

activist networks and social scenes. Many of us didn’t think about the

different meanings and risks of direct action tactics for communities that face

police violence every day. And for the most part, we were only beginning to understand

the interconnections among colonialism, capitalism, ableism, hetero-patriarchy,

white supremacy, and other systems of domination. The people most affected by

what we protested in Seattle were not majority white, and significant numbers

of Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color did participate in the

protests. Those of us who were white should have worked more intentionally in

solidarity with their efforts.

In the wake of the Seattle shutdown, longtime activist and writer

Elizabeth Martinez brought much of this to the foreground with her article “Where

Was the Color in Seattle?” Her intervention sparked valuable critical discussions about not

only the racial composition of the protests, but also the relationship between

mobilizing and organizing, strategy and movement-building, and contending with

social hierarchies as they are reproduced in movements.

These discussions illuminated that, while mobilizing for Seattle, we

didn’t sufficiently consider how to lay the foundations for a movement that

could continue to grow and learn beyond our week of protests. As a result, we didn’t

grapple with crucial questions: How should we be consciously connecting movement

efforts to ongoing community-based struggles? And how should we, in Guilloud’s words,

“challenge the dynamics of privilege and oppression while also building large,

wide, and deep movements that are led by and rooted in the experiences of

people who know injustice and exploitation – currently and historically”? These

questions continue to be some of the most pressing for movements in North

America.

The other lesson is that success almost always requires collaborative work and planning. The Seattle shutdown was neither spontaneous nor an outcome of good fortune; it was the result of months of preparation by thousands of people. We made it happen through audacity, yes, and also diligent, calculated collective effort. Seattle DAN organizer Jennifer Whitney summed this up well:

nothing came from out of the blue – we organized, and it paid off. We weren’t just freaks and artists and full-time activists on the streets; we went into high schools and churches, labor councils and neighborhood associations, workplaces and universities. Those people were on the streets with us; those people flooded city council meetings afterwards, damning the police and the city, not only for their illustrious abuses and constitutional violations, but also for having invited the WTO to meet in our city in the first place.The teach-ins, workshops, and presentations, which took place across the town for months in advance, ignited the population’s anger and propelled them into the streets, more than a single flyer or workshop ever could have.

Months of educating, mobilizing, alliance-building, training,

and planning laid groundwork for mass collective action.

What’s more, we developed a strategic framework that

invited participation and creativity. Thousands of people organized themselves

into affinity groups, crafted their own plans, and worked with other groups to

carry them out. With a shared framework and lots of communication, groups were then

able to react nimbly as circumstances changed rapidly in the streets. In the words of San Francisco Bay

Area DAN organizer David Solnit, “organized resistance

catalyzed a broader public uprising; thousands who had no direct contact with

the coordinating organizations heard about or witnessed the mass action, it

made sense to them, and they joined in or supported.” How to build this kind of

inviting organized resistance in a resilient, expansive way is another pressing

question for movements today.

What we did in Seattle in 1999 wasn’t flawless, but it was an amazing victory, one that can and should still inspire us. Let’s celebrate it, learn from what actually happened, and keep fighting and building.